The Apartment

Billy Wilder kept it simple. He didn't forcefully lure us into liking the characters, "No-no-no—why would I?" | imagine he'd say. "It's about the apartment." (That cunning fox!) And that's why, before we know it, these faces on the screen have crawled under our skin, and we are delighted that they did: we are enchanted by Ms. Kubelik, we feel pity for Buddy Boy, and contempt for Sheldrake. In different ways, we fall in love with them.

It's like marrying that platonic friend you've known for years. And when you're married (and hopefully in love), you forgive nigh everything: Baxter's lack of game, Fran's self-destructive ways, but most of all-and perhaps my biggest pet peeve—you forgive the intrinsic predictability that rom-coms at times possess. Not that I'm opposed to them achieving a gleeful closure to their arcs. Not at all; quite the opposite, I appreciate it. But knowing that they will can make the happenstance feel contrived.

But even if that's the case, as far as this flick goes, as I said, you are, indeed, in love, so you forgive that too. And regardless of how many times you've watched it, by the time she says, "Shut up and deal," a smile has flooded your face with a sweetness worthy of your favorite dessert. A taste that stays with you as you wake up the next morning, open your eyes, and can't help but think, 'What a marvelous treat!' You know, movie-wise.

Diamonds & Rust

I'm not here to romanticize Joan and Dylan's relationship. I'm not here to philosophize what "Diamonds" or "Rust" means. I'm not here to simplify the ethereality that lies between the lines—it's all there, in the song, in plain view.

I'm not here to speculate what he brought in exchange for the cufflinks. I'm not here to point out the subtle blending of percussion and guitar along the track. I'm not here to shine a light on the exotic harpsichord infusing the ballad with a "je ne sais quoi" —it's all there, in the song, in plain view.

I'm not even here to retell stories of what she or he has said about the tune throughout the years. Not even to comment on Joan's glorious voice. Not even to discuss why or if Dylan was the "original vagabond"—it's all there, in the song, in plain view.

No, that's not what l'm here for.

What l'm here to do is to highlight what I believe is one of the most loving, hurtful, and perfect verses ever written on a song:

"Now I see you standing

with brown leaves falling all around

and snow in your hair.

Now you're smiling out the window

of that crummy hotel

over Washington Square.

Our breath comes out white clouds,

mingles and hangs in the air.

Speaking strictly for me,

we both could have died then and there."

That's it.

The Universality of Norman Rockwell

An accurate tale about his spacetime warping aesthetics.

I understand the plight of both the mature and fledgling souls of Latinos and Latinas bitterly, or at best logically, questioning the appellation of the fifty-states country: America.

They say, “We are America too!” I’ve said it as well. I get the feeling, being ostracized isn’t an ideal sensation. (Or rather, the taking away of what also belongs to you! Even if it is just a name… it matters.)

But it is perhaps ostracization that has allowed me to be lenient about the matter at hand.

You see, coming from the Dominican Republic, I’ve often felt ostracized by the concept of Latin America.

It’s like, I’m not American, but I’m also not quite Latin American, given the geographic location of the island. But beyond location, it is a matter of culture, in that, being, by definition, Latin Americans, but being so close to the USA, Dominicans’ identities get diluted. Two poles are pulling, each from their respective base.

In actuality, it feels more like a pouring of information from two different faucets. Which, if you ask me, is, by all means, a blessing.

One of those blessings is the thought I started to unfold a few paragraphs ago: The mongrel mindset that springs from the aforementioned pouring of cultures helps one see with clarity that all and all, United States of America, has the word America in it.

Dominican Republic doesn’t, or Puerto Rico, or Chile, or Argentina, or Brazil, or Peru, etc. So, practically speaking, to me, is absolutely comprehensible, that Americans call themselves Americans.

I call their country, America. And I call them, Americans.

Yet, somehow, through that concession, flows a ravaging stream of ills, as well as of delights. I’m here to talk about one of those delights: Norman Rockwell.

Once you give in, and call USA, America. Once you give in, and call their citizens, Americans. Automatically, weirdly enough, what you are calling them, what they become, is: sons and daughters of Norman Rockwell. Of what he painted. Even if you’ve never seen not even one of his paintings. And when you do see them paintings for the first time, it feels… It feels like you’ve known them all your life.

Gustavo Cerati said about writing his magical anthem “De Música Ligera” that when he was penning it down, it felt as if it had been sung by thousands of folks before. Not because it wasn’t original, but because it felt, logical, obvious, imperative. That’s the vein in which Rockwell’s paintings function.

It’s beyond an aesthetic—he wrung the tail of an idea, tamed the beast, and dissected it into a concept. Of course, this might not have been a necessarily conscious effort. But unconscious or not, in that, he succeeded.

Rockwell’s America is so effing potent, that, as the best art does, you see yourself in it. Even if you’re not white, or black, or even if you don’t experience such privileges, or dangers, even if you’re not American.

(Imagine what they do if you are, indeed, American.)

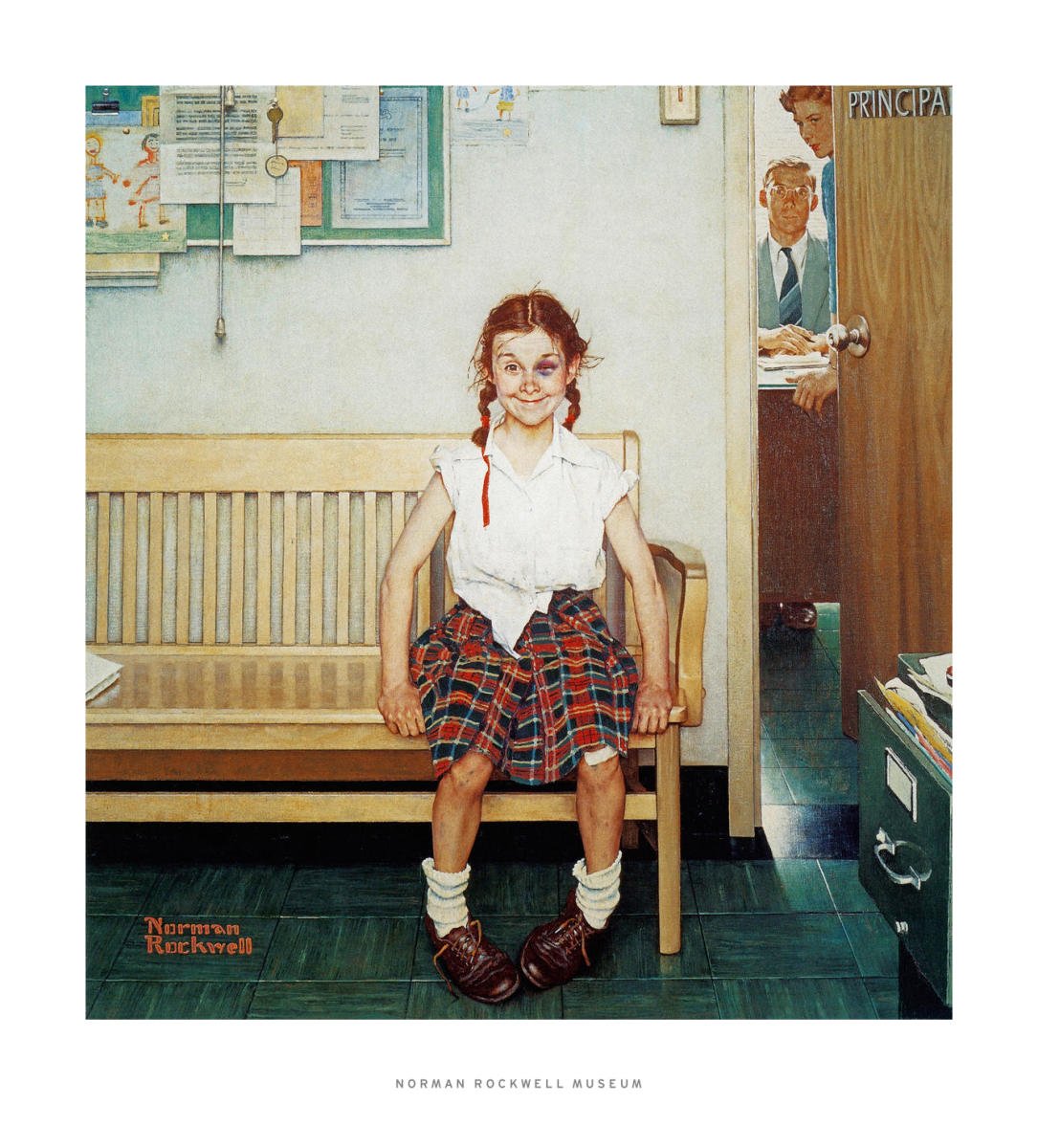

I remember seeing myself in that red-haired girl seating joyfully outside of the principal's office, with a black eye.

(I thought, That’s me.)

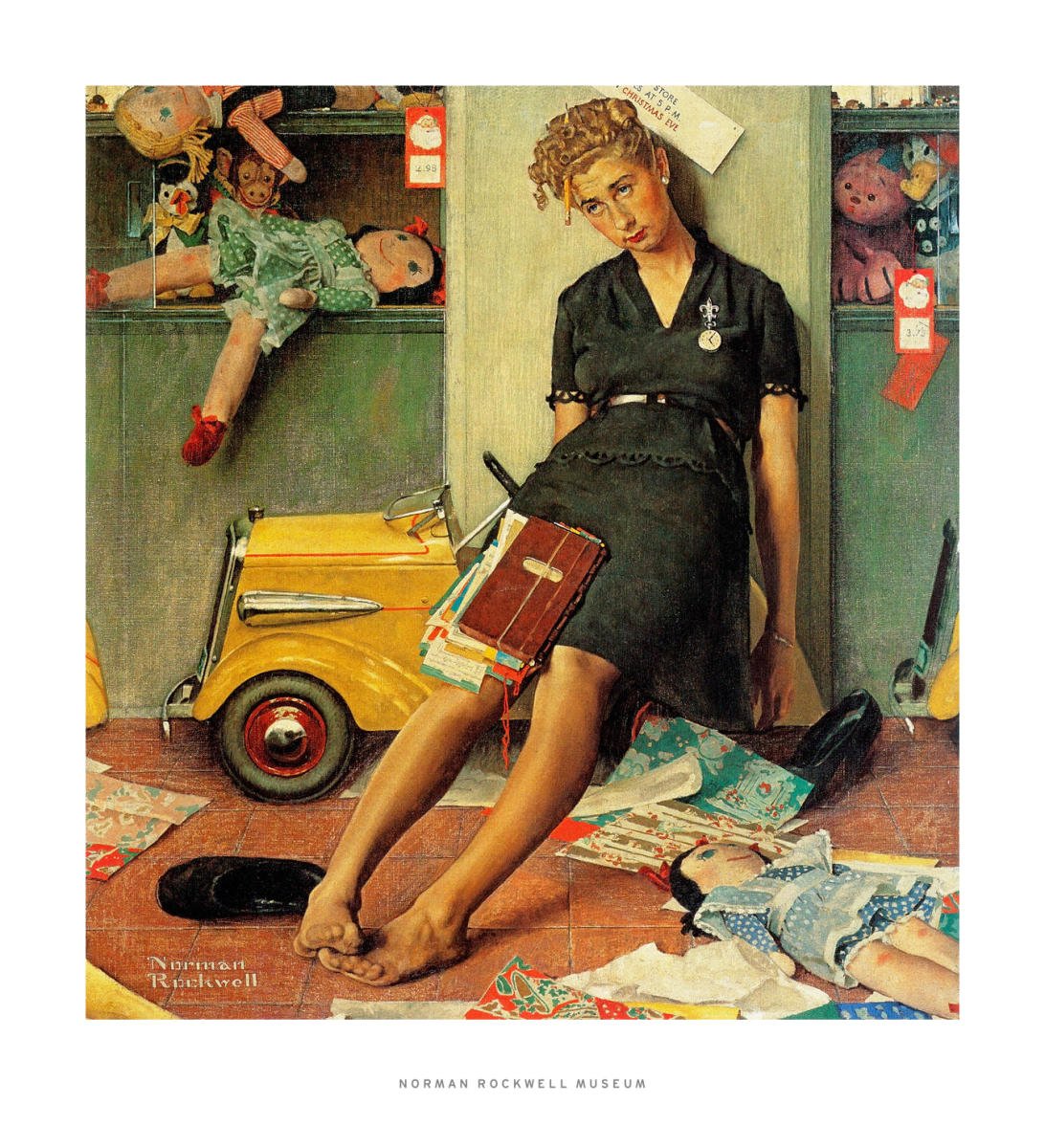

I remember seeing myself in that tired blonde sales lady on Christmas Eve.

(I thought, That’s me.)

I remember seeing myself in that bespectacled brunette with a painting brush between her lipsas she dashes with her easel under her arm and cavases and palette in hand.

(I thought, That’s definitely me.)

Those images are not innately American, but Norman made them brim with Americanism. Even the slightest of innuendos shouted “Land of the Free” with both of its lungs. And even the ones that don’t have any kind of hint, even those, you still feel it.

(Perhaps it is the notion that his other more patriotic pieces were painted by the same artist.)

His subjects are imbued with that entrancing promised land aura. It’s inescapable. And my point is: That’s a good thing.

When the book of time closes. And what survives is a selected collection of the artworks that managed to jump out their three-dimensional prison and lodged themselves in the collective consciousness.

Majestic fingers are going to peruse that book, divine eyes trying to divine what’s a worthwhile stop for a minute or so.

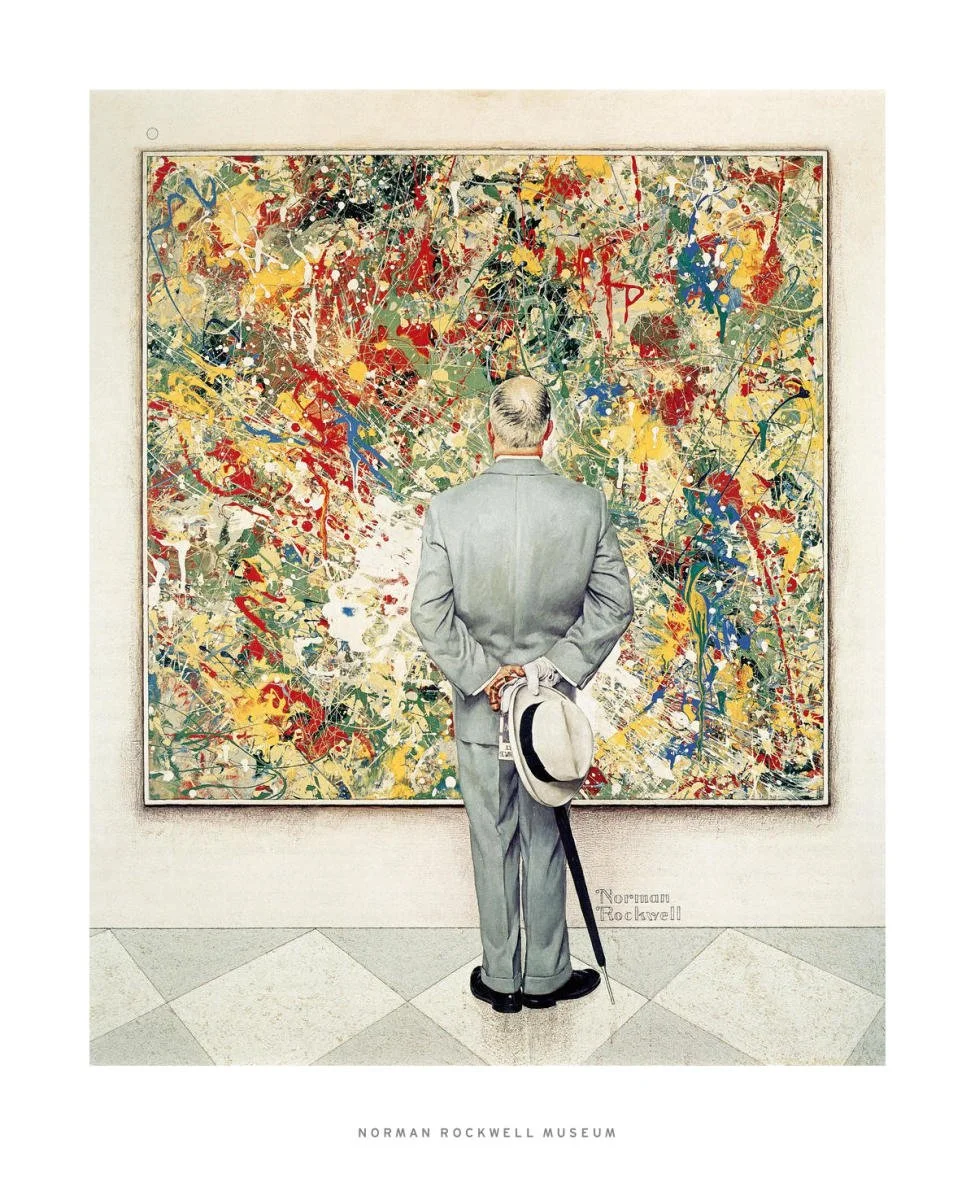

Thanks to Rockwell, those fingers, those eyes, will understand that there once was something called America. And that it was so universal, so cosmological, that even those immortal fingers as they caress the surface of The Connoisseur and lay their eyes on it, and witness the rear of a balding man with a grey suit, hands behind his back, closed umbrella and hat between his hands, and next to the umbrella, an inscription that although indecipherable to the eyes and fingers doing the perusing, you and I know it says: Norman Rockwell, and the balding man is in a museum, staring at a painting, the same way the eyes and fingers perusing the book are staring at him, and the painting the balding man is staring at is abstract, the expressionism kind, a beautiful explosion of colors, which happens to be the language of the fingers and the eyes, and so the eyes and fingers proceed to say out loud what they feel the bald man must be thinking, which happens to be precisely the same thing the eyes and fingersare thinking—and that is:

That’s me.

León:

The Professional

Recently watched it again. But before I did, I could have sworn two things. One, that the story took place in France (naturally, I thought Paris—being that I remembered happenings taking place around a city-like environment). And two, that Leon was, of course, French. In both instances, I was wrong. One, the story takes place in New York—in my defense, all the interiors were shot in France, and it shows. And two, Leon is Italian—which for some reason I found quite funny (given that both Jean Reno and Luc Besson are French).

This is not bad or good, and it takes nothing from the film. Which l've watched three times or so, and each time I do, I dig it more. These days I watch films in intervals, alternating the viewing with playing guitar, while I rest my fingers. But with this one, that was a hard task; in that I couldn't hit pause and go back to strumming, I was glued. The movie became the central purpose of my evening, the six strings ceased to be a priority. That's not to imply the film is fast-paced. It's not slow, but it ain't fast either—it takes its time with it, in the best possible way. My favorite thing about it? Luc's direction. Unimpeachable. Just wow! A few frames are tattooed on the walls of my skull.

That said, I can't stop myself from commenting on Gary Oldman. In a genius decision, his character wears the same suit the whole picture; in doing so, the attire becomes the villain's set costume as the narrative develops. The moment I love the most from his performance is when after the killing spree of the denouement commences, he asks his lackey to bring him everyone, to which the lackey, puzzled, asks back what he means by "everyone", to which he replies, "EVVVERYYYONE!" Hysterical, in a humorous kind of way. Superb, in a Gary Oldman kind of way. And right on the mark, in a Leon kind of way.

No Hard Feelings

There are songs that give you permission to laugh, to create, to cry, to dream, to fail, to achieve, to be quiet, to be riotous, to love, to unlove, to live, and to die. And I believe I'm not alone in saying that this is one of those.

And that might be the case even to the ears who haven't gone through existential journeys, carousing around alleyways of the soul not apt for the frail of heart, groping about in the darkness of dark for the slightest shimmer of light—even if that's not your bag, or fate, it is my conviction that this tune will intimately sing to you nonetheless.

To quote Camus, "Like great works, deep feelings always mean more than they are conscious of saying." This piece speaks in tongues I can hardly summon with my pen. It caresses both the bruised and nubile spirit. And glory be to the heavens for that.

It happens, you know, now and then comes a song so much like itself, that it changes your life, and in some cases, like this one, it saves it.

Run for your life (but do it slow, so it catches you)

The beautiful and terrifying effect rom-coms play in our fate.

You've felt it, haven't you?

It happens about half an hour into the movie, sometimes sooner: Endorphins clambering down your spine, and splashing all across your body, they're easy to spot.

They’re wearing prim and proper Vera Wang dresses, muddy and torn Dr. Martens boots, they sport King Leonidas’ Spartan shield (and his roar as well), and the sword? Couldn’t be other than Damocles’.

They're are to take control over your psyche like the colorful blobby thingies from Inside Out. But their hue? You have never seen. Why? Because each time, each single time, it’s a new one.

Just like Love, but this is not Love, Love is easier to handle, this is the tie Love puts on for its 9 to 5, its socks, its underwear! And as one does (or should), it changes it every day, hence your inability to recognize them.

These endorphins purpose is not to harm, on the contrary, yet they harm nonetheless.

Whose fault is that? I’m not here to cast blame. But harm they do. And they’re quite good at it—dangerously good. So much so, that if you let yourself drift into their current, you might find yourself, with no previous notice, in a romantic situation you swore you’d never be victim of—again. But that’s not always a bad thing.

Perhaps you needed that little push (you tell yourself). Maybe you needed a moving picture to jolt your heart to life (we all do now and then). To imbibe you with endorphin courage, and go after that person that, all of a sudden, you realize is the one.

O, how many marriages (and divorces) were orchestrated by the subtle and sharp insidious threads of rom-coms. How many kids have sprung from a phone call at the right time (or wrong time) dialed by the fingers of the pixie dust tossed onto you by the talent of a film script that is at times put together by a conglomerate of at least three writers, and an average director.

(That seems to be the formula for the perfect romedy; it’s rather rare to find such a film by one sole writer, and helming the boat, an extraordinary director—it happens! By all means, but that’s not the norm. And I’m not implying that it should be.)

How many kisses, hugs, orgasms, moans, sweat, and complaints from neighbors—how many small mercies we owe to this complex yet undoubtedly magical communication apparatus that are romantic comedies.

You might think I'm overreacting, I feel it in the tennis-match motion of your eyes gently smashing that ball from sentence to sentence. You might think these kinds of films are not that deep, not that powerful. And if you do, that’s only natural.

Because, although the sensation portraits an eternal veil, it is fleeting. And like a dream, you forget it. What you don’t forget is the decision you made in that instant when the rush was at its peak. You saved it for an afterthought, in the back of your mind. You might not end up liking the movie, in most cases, that’s the actual outcome; the spell fades, it sizzles as the plot develops. But that decision, whether wise or dumb, is already tatted on the fabric of your future. You will follow through.

That scene, that chemistry between the characters, that funny remark, that voice-over, that montage, that ridiculous speech, that coming together of the plot, that experience, it discombobulated your ethos, it opened a new door. And you will go through it. Even if you know what’s behind it (and may the heavens be with you in that endeavor).

Surrendering yourself to whatever is happening inside of you while you’re watching these films, is not an act of bravery; you’re not proving anything, you’re being proved. And there’s no shame in that. Because, as far as human nature goes, there’s only so much we can do, given that, you know, we are humans.

Still, I’m reminded of Kate Hep line to Bogie in The African Queen, “Nature, Mr. Alnutt, is what we are put in this world to rise above.”

Me, I’ve been a victim myself, most definitely, and who knows, I might be a victim again.

I’m partial to the genre, indeed I am, but I’m aware of its perils. No other kind of film creates a more convoluted mental state.

No action film, even when you leave the theater throwing kicks and punches, or if it was car-related, pushing the pedal hoping flames would pour out your vehicle’s muffler—even that, it doesn’t come close.

No gangster film, that has you questioning the morality of your righteous life and if it’s worth it, the allure of crime envelops you for a few seconds, the temptation is frightening—even that, it doesn’t come close.

No inspirational film, that has you believing all of your dreams are possible (and they are), and you cry, an ecstatic ride, insurmountable happiness—even that, it doesn’t come close.

No horror film, that has you seeing shadows, ominous figures, and hearing indecipherable noises all over your house, it has you checking under the bed, and sleeping with the light on—even that, it doesn’t come close.

No auteur film, with its pizzazz and nuances, making you stretch muscles of feelings you didn’t know you had, reshaping the lens with which you glance at reality and what’s important—even that, it doesn’t come close.

No film noir, with its unfamiliar yet recognizable palette of colors and characters inviting you to join them in a seemingly monotonous adventure, then revealing itself to be a whole new dimension with a particular language, a particular meaning, a particular elegance, that makes you want to jump into the screen and put on a trench coat, a fedora, and smoke amidst the heavy rain until you crack what needs to be cracked—now that, comes close, but still, not quite.

Rom-coms are a realm in which love is king. And nothing, no one, nada, zippo, can beat love. And even less, when you’ve concocted it with a reasonable dose of laughter. Check the ledger of the collective conscience and tell me I’m wrong.

The alchemy produced by these movies is capable of the incapable. It softens a heart. It hardens a wavering will. It straightens the hunch of the gut. May we all know how to put into practice the intricate and mindful manner in which one ought to react when it knocks on our door—which is:

Letting out a huge sigh, smiling with relief, and helplessness, inviting it to come in, and timidly but genuinely confide, “I’m glad you’re here.”

Cape Forestier

I'm convinced: Sundays were invented to listen to Angus & Julia. Or alternatively, if you desire to turn every other day into a Sunday, listen to Angus & Julia. I know, you know, we all know music is ethereal, but few are the cases that statement is better exemplified than in these two, in this album.

It's a bluesy breeze punching you in the gut. It's a fortuitous glitch in emotions' vocabulary. It's a kiss that comes from somewhere around the cosmos, and you, inadvertently, stole it and made it yours.

And if that's not what a Sunday feels like, pardon me, I'm wrong about this whole assessment. But if I'm right, Angus & Julia make magic, not music. And "Cape Forestier" is just another delicious proof of that.

Trouble is a Lonesome Town

Most of the time I tear up listening to music is not because of the emotionality of the tune. It's hard to pin down the reason, but I believe it has to do with a chord being struck in my insides. Or perhaps it is a striking match with my personal aesthetics. Or maybe it is just because the piece is too effing good. Lee Hazlewood, with this LP (his debut), made my eyes sweat.

This is a concept album, released in 1963. I'm not sure if folks knew such a thing was doable back then. But Lee did it. And he did it tackling themes in a way that even by today's standards is revolutionary. But who cares if he's still innovating 60 years later? What matters is: Does it deliver? Is it good? Does it work? A question I will not answer, at least not directly.

It's no wonder he's developed a devoted cult following in recent years. If you get what he's about, you're about what he's out to get. His voice and lyrics hook you into his world, they draw you into Trouble, a lonesome yet remarkable town. Songwriting at its finest: funny, irreverent, profound.

Thank you, Lee Hazlewood, for having visited Earth.

P.S.

He released a companion EP with this project. It's called "Autobiographie." And it's brilliant.

Diddy’s Video: What now?

His domestic violence security recording brings forth a conflicted conversation about hip-hop.

What now? I ask myself.

And I’m not talking about if Diddy would be convicted for the crime. That question is being asked and answered as we speak. So, no. I’m not talking about that.

I’m talking about me: What now, when his songs pop out in my playlist? I’m talking about you: What now, the next time you catch yourself Diddy bopping?

I’m talking about him, and the asphalt-ridden knot that harrowing video left in all of our stomachs.

I’m reminded of a Dylan line: “Zapruder's film, I've seen that before. Seen it thirty-three times, maybe more. It's vile and deceitful, it's cruel and it's mean. Ugliest thing that you ever have seen.”

I’ve seen the video more times than I care to admit. It ruins my day in a way that not even his songs can fix. And no, I’m not talking about his solo songs. I’m talking about the dude’s voice as a hype man on 5 of every 10 hip-hop classic tunes between now and the 90s (that statement might be hyperbole—but it might not).

You can say what you will about the guy, and rightfully so. But as far as hyping a rapper on wax, there has never been, or ever will, someone better than Sean “Diddy” Combs. And everybody knew it.

It’s a seal that rappers wanted even if they didn’t need it. Even after his time on the Sun as a musical giant had passed, the best of the best would still reach out to him for a taste of the cachet provided by his senseless ramblings before, after, or at times blatantly in the middle of the artist’s performance.

And it worked, every single time; by talking, about everything and nothing,he made the song better—such is the peculiar realm in which hip-hop dwells: shouting threats, or murmuring prayers, or just talking to talk, his voice did the trick.

And that wasn't because his voice is particular, but because… it was Diddy’s.

And whether consciously or unconsciously, we knew, Diddy's unusual vocal input started alongside the coolest voice rap has ever heard, which happened to stem from the throat of the most skilled rapper of all time, the greatest of them all they say, immaculate cadence, flawless delivery, impeccable storytelling, the king of New York, Frank White, The Notorious B.I.G., also known as Biggie Smalls: Christopher Wallace.

And every time Diddy did his jawing on an instrumental, it struck a chord, it reminded us of BIG, and how aside from the music, Diddy was the only living and active fixture we had to remember Biggie by.

(That is, aside from Hovito, of course.)

Whether Biggie made Diddy, or Diddy made Biggie is a conversation I’m not attempting to have. The only certainty is that he was on almost every one of Frank’s songs, including the best ones.

From the epic phone conversation on “Suicidal Thoughts,” to his borderline intrusive adlibs all the way through “Juicy.”

From the genius interlude on “Big Poppa,“ to his kiddish epilogue on "What's Beef?”

From the fateful intro on "Going Back to Cali,” to the resolute outro on "Long Kiss Goodnight.”

He was on everything.

And this invokes the question, what does this say about hip-hop?When the producer of at least two of the greatest albums of the genre (one of which recently landed on Apple Music's 100 best albums of all time) is shown beating the living no. 2 out of his partner at the time.

And I'm aware that as seminal as Ready to Die and Life After Death are, and seminal they are indeed, they are far from being the whole list of the domestic-abuser accomplishments. However, for the argument at hand, those albums will suffice.

And that argument is as follows: What does Diddy’s video say about hip-hop?

The answer is: Nothing new.

And I mean that, of course, in a bad way, but also in a good way.

Hip-hop, the music genre, is, at its core, extremely primal. And this is its greatest strength, and weakness.

Take the Kendrick and Drake beef, entertaining as it was (even needed you could argue), at its bare bones, it was exuberantly childish, which is what hip-hop is.

(I mean that literally, in that, the genre is precariously young, and that has plenty to do with my current assessment.)

But again, that's what tickles the spark that produces the fire: that raw, unbridled, and primitive fire. Which, we depend upon to survive.

"War. The final argument of ungrown men,” Bukowski would say. We all know war is hell. But not everybody dares to say that there’s beauty in war, but there is.

And not only that, we crave for that war-beauty—not the war! That’s horrendous, worst even that what we witnessed in that video, and that’s saying something.

But the fact of the matter is that we don’t think about the horror when we are witnessing the beauty, and vice versa, we don’t think about the beauty when we are in the midst of the horror.

Frank Hebert, Dune’s author, said it best: “Isn’t it odd how we misunderstand the hidden unity of kindness and cruelty?”

That kindness and cruelty is never more present than in a child. And hip-hop is a child.

It may not stay that way forever, most likely it won’t, but as of now, it is: Ungrown men and women at the trenches, killing each other for a cause so foreign to them that they couldn’t tell it to you if their life depended on it, and it does.

Savages, brutes—monsters you could deservedly say. But they are also soldiers.

(I say that in the most honorable way possible. And these soldiers’ cause, whether they understand it or not, couldn’t be nobler.)

Some of whom, if you point toward their household, you may want to lock them away for life.

But a soldier in jail is still a soldier, just as a criminal out of jail is still a criminal (at least until it serves its due time).

Diddy is no soldier, and Diddy is not hip-hop, not even close: no one man is, or woman, or individual.

But if hip-hop was indeed an individual, a human being—would you send it to jail?

I love hip-hop to death, and it pains me to say this, but I would.

Because, when I see Cassie’s video, I see hip-hop in there. It’s not in the violence per se, it’s not in Diddy, it’s not in Cassie.

It is not there, but somewhere in that recording, there’s a side of that undeveloped genre that tried to find its way into the mainstream, and after it did, it tried to maintain it, by any means: it mattered little to none who or what gets in the way, ”I, hip-hop, will get my way.”

And it said that before, after, or at times blatantly in the middle of an artist’s performance: shouting threats, or murmuring prayers, or just talking to talk—hip-hop’s voice did the trick.

Yes, I would send it to jail, whatever that means.

But I would also give my life to keep it from getting there.

That’s the duality of the human condition.

One can only hope that with time, the evils are less evil, that miracles happen more often, and that the art is able to soar over the frailty of individuals.

This genre is not perfect, it might be the farthest from perfect that any other, and often enough, its players do not help in that regard.

But that’s not the big picture. The one that matters. The one I can’t paint with words. The one you’ve got to feel for yourself. It’s there, in the remnants of the war, that imperceptible beauty we at times have to squint our eyes to perceive.

Yet, at other times, it’s so bright we are blinded by its grace.

If you haven’t already, you’ll know it when you feel it.